Dr. Strangelove: Both Lovable and Strange

In 1963 the threat of nuclear annihilation, nowadays seldom discussed or considered, was a popular mania. At that time the two “superpowers” of international politics, the United States and Soviet Union, were engaged in an irrational buildup of nuclear weapons, each in the phantom hope of deterring the other from attempting a first strike.

U.S. President John Kennedy and Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev had engaged in various acts of one-upmanship and defiance, most notably the Cuban Missile crisis and the Bay of Pigs invasion. In the previous decade an anxiety-ridden populace had been warned about the possibility of having to take refuge in bomb shelters in the event of a sudden nuclear assault. The U.S. Interstate highway system, in fact, had been financed and authorized by President Eisenhower not for civilian use but as a supposed safety measure to evacuate large cities quickly during nuclear war.

It was within this crucible of political tension and mistrust that 35-year-old movie director Stanley Kubrick, fresh off his adaptation of the controversial novel Lolita by the Russian-American author Vladimir Nabokov, dared to dramatize an even more controversial Russian-American outcome: the real possibility that at any moment, due to a crass clash of Cold War egos, all the life on earth might be destroyed by a sudden mass detonation of bombs.

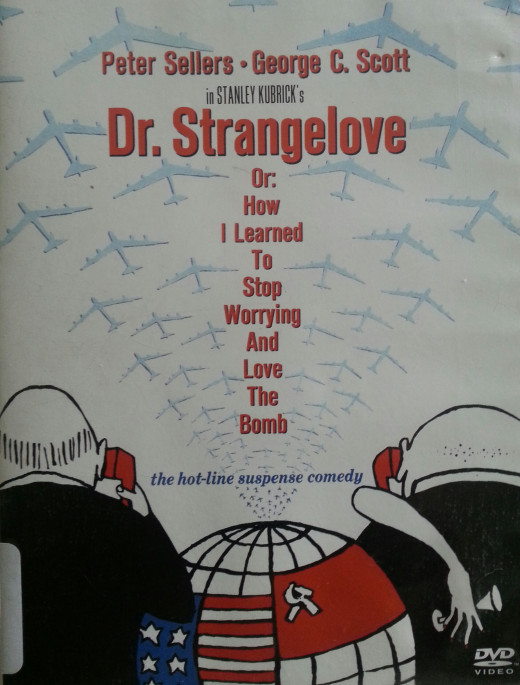

Kubrick, a former staff photographer for Life magazine, had already achieved a stellar reputation for craftsmanship and literate storytelling in his direction of the World War 1-era drama Paths of Glory (1957) and the historical epic Spartacus (1960) in addition to Lolita (1962). For his latest project, as both producer and director in total control of content, he chose as unorthodox an approach as any artist had ever taken: to dramatize the most frightening and morbid subject in contemporary life as a comedy. Its very title was shocking in its irony: Dr. Strangelove, Or How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

Never has a gamble paid off with such fantastic success. For the resulting movie stands as the greatest satire in the history of the medium: a tableau of one visually iconic scene after another under the careful arrangement of Kubrick’s photographic eye, and superb performances by the quartet of Peter Sellers (in three different roles), Sterling Hayden, George C. Scott and Slim Pickens.

In the early 1960’s a psychotic cigar-smoking Air Force General Jack D. Ripper (Sterling Hayden), a paranoiac determined to make a name for himself by defying political interference, decides to implement “Plan R”, a newly-enacted protocol which allows a lower-level bureaucrat to bypass presidential authority to initiate a nuclear attack. Filled with pathological hatred for Communists, and frustrated by his own sexual impotence which he attributes to a Communist-led campaign to fluoridate public water supplies, Ripper orders a preemptive strike of a Russian nuclear missile site. The British adjutant at Ripper’s command post at Burpleson Air Base, group captain Lionel Mandrake (Peter Sellers in the first of his three roles), is appalled by Ripper’s insanity and unsuccessfully attempts to pry out of him the three letter code necessary to abort the mission.

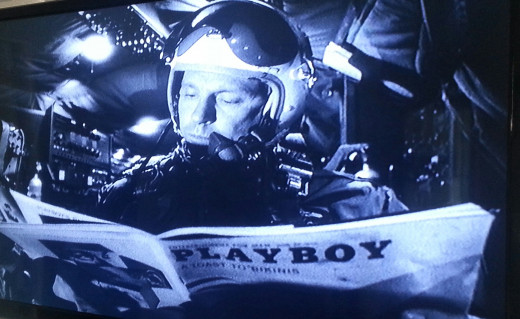

The bomber captain of one of the B52’s that receives the attack message, Major T. J. Kong (Slim Pickens), a salty Texan who reads Playboy magazines and dons a cowboy hat in the flying seat, at first considers the order a hoax. But once he verifies its authenticity he immediately gives a stirring pep talk to the rest of his crew, promising them future glory and promotions if they successfully carry out the attack.

Back in the “War Room” in the Pentagon, U.S. President Merkin Muffley (also played by Sellers), a humorless bureaucrat, orders the mastermind behind “Plan R”, General Buck Turgidson, to explain the crisis. Turgidson, a chest-thumping champion of all things American, insists that the B52 bombers have lost all outside radio contact and already passed their “fail-safe” point in flight. An outraged Muffley summons Russian diplomat Alexei de Sadeski into the War Room and uses his hot line to call Soviet Premier Dmitri Kissoff. By mutual agreement, the two understand that the attack is a mistake and Muffley authorizes a U.S. force from a neighboring air base to invade Burpleson and overthrow the insane General Ripper.

The attack ordered by the president is successful. The troops at Burpleson surrender and a shamed Ripper shoots himself before Mandrake can coax the code out of him. However, some random doodling on the general’s notepad about his nagging obsessions with “purity of essence” and “peace on earth” lead Mandrake to conclude the code must be some combination of the letters “P”, “O” and “E”. Mandrake persuades a capturing American soldier to allow him to make an emergency long distance call to the president to give him the news.

President Muffley gives the code and all but one attacking U.S. plane, the one captained by Major Kong, aborts its mission. Kong’s plane, damaged by a Russian missile, has lost base contact and hovers below radar surveillance. Though in danger of crashing, Kong insists on attacking an auxiliary target and manually dislodges the missile and rides it out of the bomb hatch when the hatch doors malfunction.

Russian Diplomat Sadeski informs President Muffley that any preemptive strike will result in the unleashing of a new Soviet-designed “Doomsday Device”, which will automatically destroy all life on earth and result in a radioactive cloud lasting 93 years. A former Nazi nuclear physicist, Dr. Strangelove (Peter Sellers), who now works for the U.S. Government, explains that extended survival is possible in deep mines and imagines important government officials, served by a complement of ten lovely young female concubines per man, repopulating the earth in another generation. General Turgidson begins fearing the Russians may try to win unfair advantages in the mine shafts and Diplomat Sadeski sneaks away to take secret photos of the War Room. When Kong’s missile explodes, the Doomsday Device is detonated and results in nuclear holocaust.

Kubrick was able to mold the performances of the cast into the furthest reaches of stereotype that would sustain credibility. These characters are disturbing on the one hand and amusing on the other because we recognize how eerily suggestive of reality their attitudes, prejudices and vanities are. Notorious for being dictatorial, Kubrick clashed with George C. Scott because the actor thought his performance was excessively caricatured. The director appeased the star by matching him in chess during filming breaks and promising him he would use more moderate takes, a promise he broke. The climactic scene with Pickens riding a missile rodeo-style required over one hundred takes. Years later, when Kubrick wanted Pickens to play the role that ultimately went to Scatman Crothers in The Shining, Pickens refused unless he was told his scenes would be done in under a hundred takes. Kubrick refused to make that promise.

Dr. Strangelove is a towering achievement, not only as a movie, but as a piece of propaganda that may have changed the history of the world in a way no other production has. When viewed from the hindsight of over fifty years, the notion that two empires might destroy the entire planet out of power-lust seems incredible. But part of the reason why is that this film portrayed the absurdity of what Dwight Eisenhower called the “Military Industrial Complex” so graphically that it resulted in the ultimate restructuring of that complex. For no one who saw this satire, either then or now, could remain indifferent to the behaviors it ridiculed.

We don’t know what might have happened without Strangelove. But we do know that in its aftermath no nuclear device of any kind has ever been used, and the fear of nuclear war in the younger generations of today has almost totally disappeared.

© 2015 James Crawford